About The Project

This page details the results of research conducted as part of UCL STEaPP’s Masters of Public Administration programme, by July Galindo, Jessica Lis, Sarah Turner and Simon Turner. It was carried out in conjunction with the Open Rights Group and PETRAS Internet of Things Research Hub.

Google recently announced that they are intending to acquire Fitbit. Despite careful messages from both parties about the fact that personal data “will not be used for Google ads,” there was an almost audible groan from Fitbit users across social media, as they collectively realised that some of their most personal data would be moving within the Google family – regardless of their views on the matter.

But, what can these users do? Surely there must be a way to control where, and on which devices, your data is used?

In theory – if you are in the European Union, at least – the answer is “yes!”.

In theory.

The right to Data Portability (RtDP) under Article 20 of the GDPR, is one of the lesser-known rights given to the data subject in the GDPR. RtDP gives a user the right to transfer personal data from one data controller to another. When used alongside other rights – particularly the right of erasure (Article 17 GDPR) – this right should enable users to be able to extricate their data from services that they no longer want to use, and move that data to a new service.

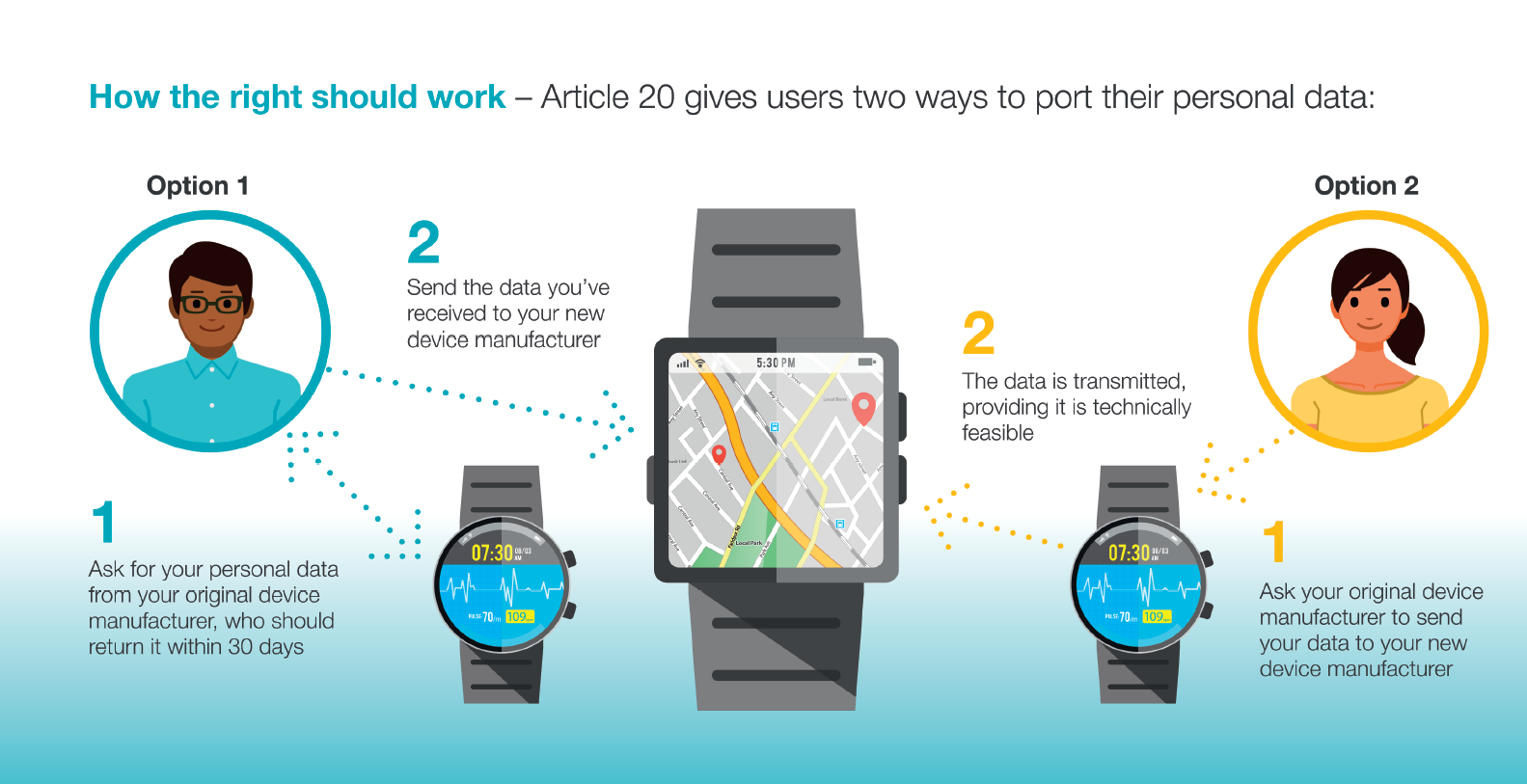

There are two ways in which the GDPR envisages data portability to work. In the first, the data controller must, without hindrance, provide the user with their personal data in a structured and readable format in order to transmit that data to another controller. In the second – where it is technically feasible – one data controller must send data directly to a second data controller when the user asks.

Data portability is a new concept, with less empirical research than other, more established, rights of the GDPR – such as the right of access (Article 15 GDPR). In particular, research in the context of the Internet of Things (IoT) has so far not been conducted. Data portability may be particularly important in the IoT, as personal data is key to making a device smart. Users may be unwilling – or unable – to change from unsuitable or unsupported devices because of the amount of data that they have provided to it.

We researched the status quo of the RtDP in relation to consumer IoT products available in the UK.

Our research had three strands:

- An experiment to identify the ability of a data subject to exercise their rights under Article 20, by creating data profiles on commonly used IoT devices (two fitness trackers, two smart speakers), and trying to exercise the right ourselves

- A review of 160 privacy policies to understand how companies involved in the IoT space in the UK provide information about the means a user should exercise the RtDP

- Interviews and focus groups, with 50 people across three different groups - users, policymakers and industry and academic experts - to understand the perception of the value of the RtDP in relation to IoT.

Our Findings

A detailed overview of our device experiment can be read here.

We tested four commonly used IoT devices and found that it was possible to get certain amounts of personal data from the data controllers. That is where the success ended. It was not possible to move the data from one device to another, and we were told by the data controllers that moving data directly from one device to another was not currently possible.

The privacy policies of IoT vendors that we reviewed showed very little detail as to how to exercise RtDP is provided. Only 39% of the privacy policies we reviewed mentioned data portability, and even further to that, not a single privacy policy made any mention of importing personal data into their service. There was no explanation of the way in which the data controller would ingest data provided as part of an exercise of RtDP.

The interviews showed, on the whole, that individuals did not realise that this right existed, but once aware, would be keen to use it, should they find an opportunity – although many were not sure that the data that IoT devices collected about them was sufficiently valuable to warrant the effort. Experts lauded the intention, but highlighted the significant technical issues that would make direct ingestion of data hard in particular without further standardisation or concerted industry efforts.

What now?

It is difficult to see how Article 20 can be successful without users pushing for the ability to move their data between controllers. If individuals believe this right to be valuable, they will have to start asking for it!

We have set up the Twitter account @portmydata as a means of promoting the right, and amplifying users’ experiences of the portability experience.

Have you tried porting your data? Would you like to try porting your data, but don’t know where to start?

Tweet us and we can share your story, or point you in the right direction.

Page last updated: 25 November 2019